By the Editor, Allan Hogan, Bulletin 6/2023, August

Stories about Frank Hurley have graced the pages of the Bulletin on many occasions. In the April 2008 edition, Rod Holtham recorded that James Francis Hurley was born to Margaret and Edward Hurley at Glebe on 15 October 1885. He was known as Frank and attended Glebe Public School. Holtham wrote ‘he was interested in photography and showed a flair that few possessed, purchasing a Kodak box camera for fifteen shillings when he was about 20 years old. At the age of 25 he held an exhibition of his work and was noticed by the famous explorer Douglas Mawson, who twelve months later invited him to be the official photographer on the Australian Antarctic Expedition.’

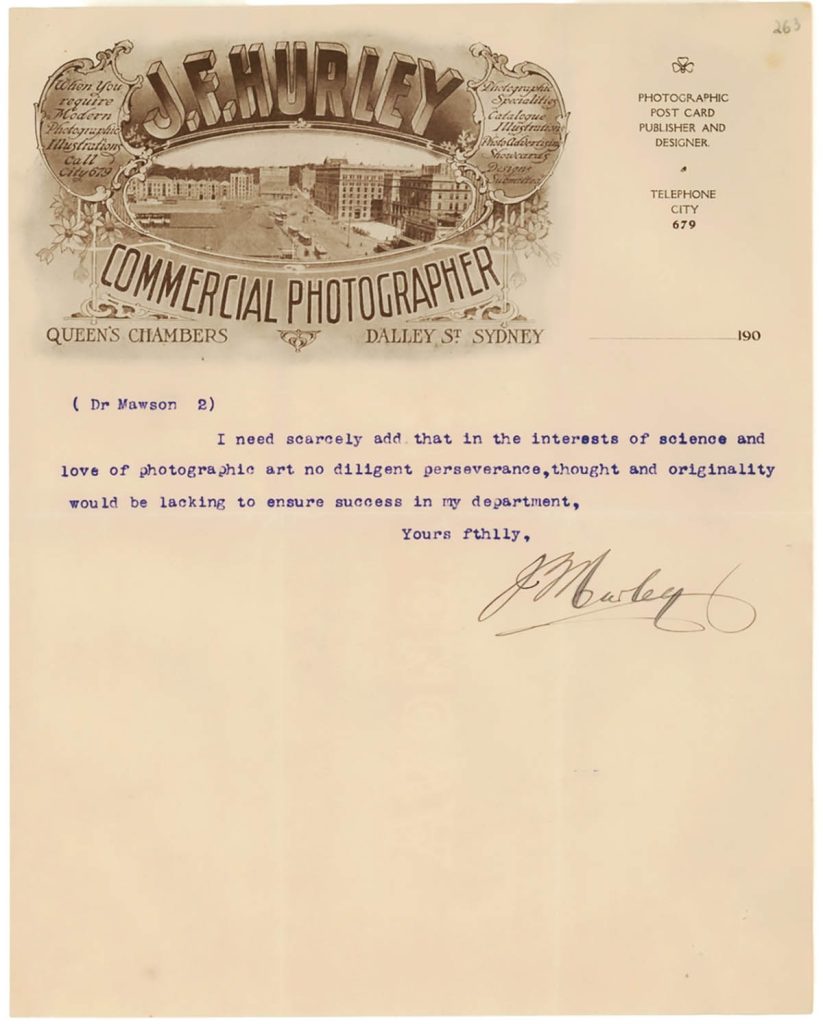

In response to an article about Douglas Mawson in last May’s edition of the Bulletin, Glebe Society member Wayne Carveth was prompted to send a copy of a letter that Hurley wrote to Mawson in September 1911. Hurley wrote that he was ‘desiring of offering my services as photographer and kinematographer to the expedition’ and that he was ‘26 years of age, unmarried, and have had a good share of “roughing it”’.

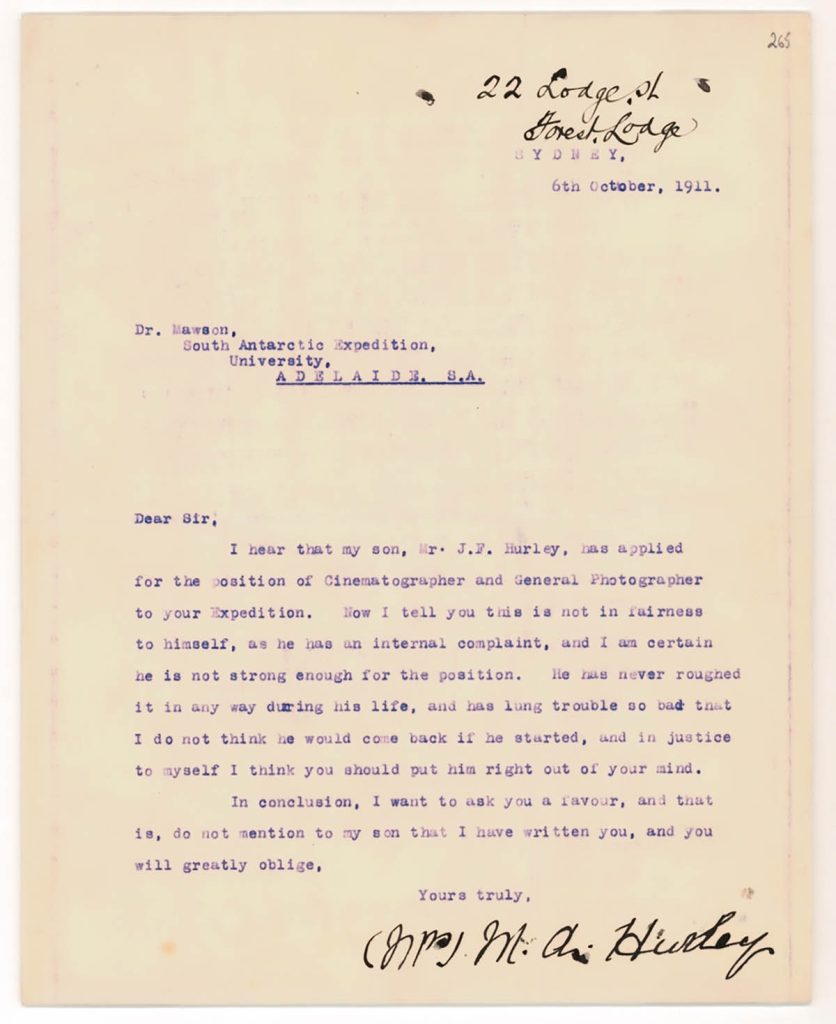

History records that Hurley got the job, but it seems that his mother didn’t want him to go. In a letter dated 6 October 1911 and written at 22 Lodge Street Forest Lodge, apparently on the same typewriter as the one her son used, Margaret Hurley wrote to Mawson that her son’s application

is not in fairness to himself, as he has an internal complaint, and I am certain he is not strong enough for the position. He has never roughed it in any way during his life and has lung trouble so bad that I do not think he would come back if he started, and in justice to myself I think you should put him right out of your mind. In conclusion, I want to ask you a favour, and that is, do not mention to my son that I have written you.

Letters to Mawson from Frank Hurley and his mother (Images: State Library of NSW)

Mawson’s reply, if there was one, is not on the record, and Hurley went on to be a member of a number of expeditions to Antarctica. He was the official photographer on Sir Ernest Shackleton’s Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition which set out in 1914 and was marooned until August 1916; Hurley’s photographic kit for the expedition included the primitive movie camera, a glass plate still camera and several smaller Kodak cameras, along with various lenses, tripods, and developing equipment, most of which had to be abandoned with the loss of their ship Endurance in 1915.

Hurley served as an official photographer with Australian forces during both world wars. His work was controversial because he believed that it was sometimes impossible to capture the scope of an event with a single photo. He adopted a practice common with photographers at that time of producing composite images by superimposing one image on another. The official AIF historian, Charles Bean, called these ‘fakes.’ But many of his war photos were iconic, without the need for superimposition.

In later years Hurley photographed the construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge and wrote and directed several dramatic feature films, including Jungle Woman (1926) and The Hound of the Deep (1926). He also worked as cinematographer for Cinesound Productions where his best-known film credits include The Squatter’s Daughter (1933), The Silence of Dean Maitland (1934) and Grandad Rudd (1935).

In 1918 Hurley married Antoinette Leighton, an opera singer, and they had four children. Born in 1919 their daughter Adelie Hurley was known as a pioneering woman press photographer. She said her father had a huge impact on her; she believed that ‘it was inbred … born within me to become a photographer. I think it was a destiny. To me, he was the master, and to have his approval meant the world to me’ (Australian Story 2001).

Adelie was one of only three Australian women press photographers working in her time. She was fearless in pursuing her shots, and also fearless against the gender discrimination of her field, lasting over two decades in press photography. Her photographs include a diverse range of subjects, from army photography, vice squad busts, life at outback stations and taipan hunting.

Sources: Australian Dictionary of Biography, Vol 9 1983; Martyn Jolly (1999) Australian First –World – War photography Frank Hurley and Charles Bean, History of Photography, 23:2; The Australian Women’s Register, https://www.womenaustralia.info/biogs/AWE5989b.htm

There are no comments yet. Please leave yours.