This article is the last of three drawn from Max Solling’s moving address at the 2024 Anzac Day ceremony at the Glebe War Memorial. See also the full text of Max’s address.

The War Memorial Movement

Australia’s response to the horrors of World War I following the Imperial government’s decision that there would be no repatriation of bodies, was manifest in the proliferation of memorials across Australian landscapes. No community was untouched by the loss of young men who had gone to war and did not return. The ‘war memorial movement’ manifested the grief and pride these communities experienced in the face of such loss.

After 1918, local communities across Australia designed and built war memorials, most being created and funded by civic committees. These artefacts took many monumental forms. Ken Inglis and Jan Brazier’s Sacred Places (2008, 3rd edition) is a memorable reading of these Australian monuments and an evocation of the culture of the First World War. In a population of more than four million people in 1915, the number of memorials in Australia is extraordinary: 516 in NSW and 1,445 across the country. A few were built during the war but most were built in the decade following the Armistice.

Local War Memorials

Seeking out these ‘sites of memory’ helps us understand the complex impact of the First World War on our cultural history. A journey of discovery might start with the sculptures of English-born Gilbert Doble (1880–1974) who chose the symbolic woman over the fighting man for his monuments at Pyrmont-Ultimo, Leichhardt and Marrickville. For the war memorial at Union Square Pyrmont, Doble created ‘Peace’, a winged female figure with shield, and for Marrickville, ‘Winged Victory’, a bronze-winged female figure. ‘Peace’ also features at the Leichhardt monument, moved from near the Leichhardt Town Hall to Pioneers Memorial Park. Doble was the first to employ a hammered bronze method to create these figures, cheaper than traditional casting.

Wives and mothers of soldiers chose a drinking fountain to be installed near a Woolloomooloo wharf ‘to commemorate the place of farewell’ where diggers boarded troop ships heading to the European conflict. Another drinking fountain on a pedestal can be found at Loyalty Square Balmain; the sandstone pedestal supports tablets and a prominent mounted light on an iron frame. Unveiled in 1916, this monument records the names of men who died at Gallipoli and features the words ‘Peace, Honour, Empire and Liberty’. And at Redfern Park, a magnificent granite monument was installed, adorned with two striking carved marble figures – an Australian soldier and a young woman holding a scroll.

The Cenotaph in Martin Place is the centre point of Sydney’s Anzac Day with its bronze soldier and sailor by the doyen of native-born sculptors of statues, Bertram Mackennal (1863–1931). Marchers on Anzac Day moved in impressive columns of twelve down Martin Place, parted into sixes after Castlereagh Street, and as they reached Pitt Street, removed hats, held them over hearts, and turned their heads towards the wreath-laden Cenotaph. This monument provoked the spontaneous creation of a new ritual, the dawn service, commemorating that dawn of 1915 at which the landing at Gallipoli became a visual metaphor for the beginning of Australia’s nationhood.

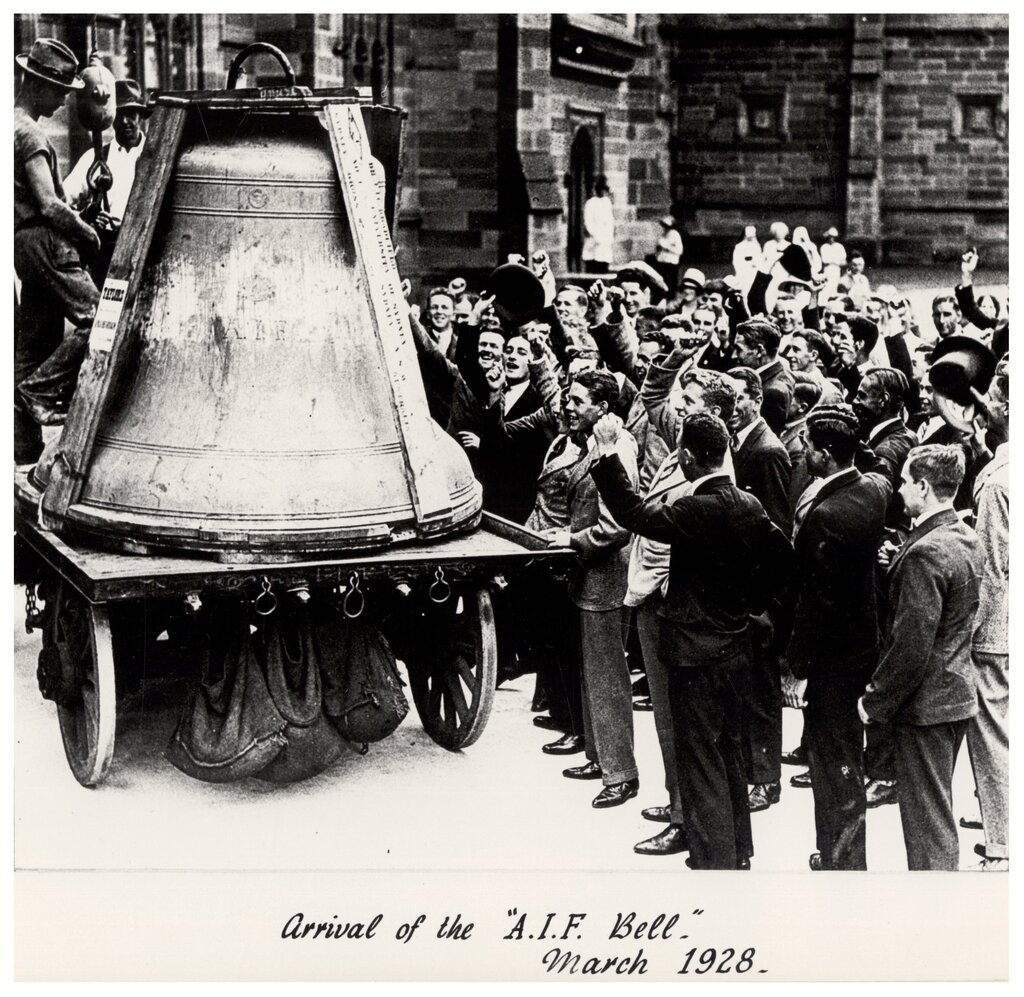

A major crowd-funded project, the Sydney University War Memorial Carillon, opened on Anzac Day 1928. Two bronze memorial walls were dedicated to the 197 Sydney University undergraduates, graduates and staff who died during the First World War. The Carillon’s 49 bells, cast in England, were carried by horse and cart from Woolloomooloo Bay wharf to the University’s clock tower and installed at a cost of £17,380. The Carillon’s four-and-a-half tonne great bell was dedicated to the AIF and named the ‘AIF Bell’.

Annandale’s monument in Hinsby Park fronting Johnston Street is a unique type of shrine. A four-metre-high Bowral Trachyte obelisk and plot of remembrance embracing an ‘ersatz grave’ representing their dead, it is flanked by seating curved forward in a quadrant plan. The obelisk was the creation of stonemason Frederico Gagliardi.

Camperdown Sailors and Sailors League lost their Council in 1909 but did not forget their war dead. Located in Camperdown Park, the bluestone monument is surmounted by a marble figure of a soldier with a rifle. And tram workers at Rozelle Tramsheds who had died in WWI were represented by the figure of a soldier holding a rifle with a bayonet, cast in white cement. ‘Erected by their Comrades’ in 1916, this sculpture by Edwin McGowan is believed to be the first to depict a digger at a workplace.

The early days of the Glebe War Memorial

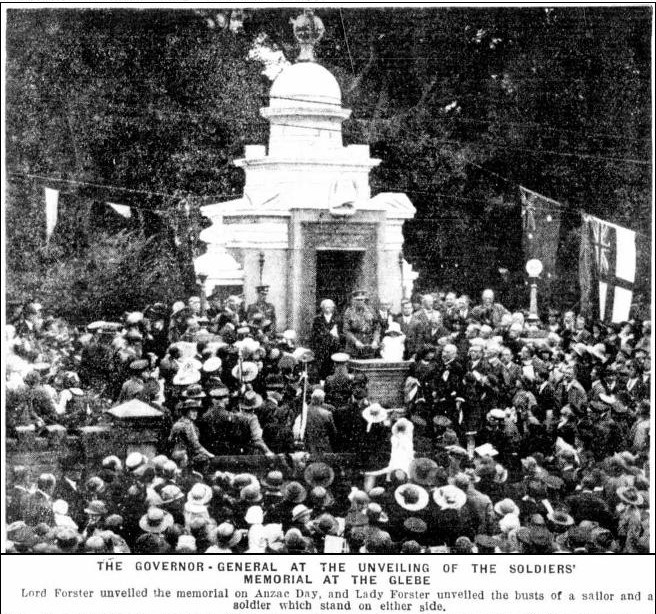

Glebe’s Kiama trachyte and marble mausoleum, 102 years old on this year’s Anzac Day, was designed by architect, anti-conscriptionist and Glebe alderman William Martin. A very Australian monument, neither the Empire nor Britain is represented in the mausoleum. Stonemason Alessandro Casagrande, who emigrated from the Veneto region in Italy, sculpted the busts of the soldier, sailor and Carrara marble angel that guard those symbolically resting in the mausoleum. Under the guardian angel is a simple and understated dedication: ‘Erected by Glebe Residents in Memory of the Glorious Dead’. An entirely local initiative, residents paid £2,964 for its creation.

A meeting chaired by Glebe Mayor Finlay Munro on 4 April 1919 agreed to create a memorial to Glebe soldiers who died. A six-member committee of Council employees and residents led by Tom Keegan (president), Tom Glasscock (town clerk) and Bill Brown (honorary secretary) began compiling names of those who died and opened a bank account for monies raised to pay for a cenotaph shrine.

Governor General Forster unveiled the Glebe memorial on Anzac Day 1922 and Rachel Forster unveiled the busts of the soldier and sailor on either side of the central shrine. This formal ceremonial occasion was described by Lord Forster as a ‘day of triumph and of glory, rather than a day of mourning’.

All these physical, emotional and artistic artefacts testify to the catastrophic character of WWI. Throughout the war pageants, processions and celebrations were regular features of the Glebe landscape. Processions along the suburb’s main artery were brightened by bands, banners and sashes.

Glebe’s paramilitary organisations encouraged a sense of participation. A September 1916 Daily Telegraph article titled ‘Glebe Fighters Home’ recounts a ‘street procession and carnival’ at which the Glebe Cadet Band and the Police Band, flanked by local councillors, led a rowdy public welcome to returned men travelling in decorated cars. Two weeks later, a carnival organised by the Glebe Local Distress Society greeted more returned men.

Anzac Day services were conducted at the Glebe War Memorial in Foley Park from 1922 to 1948. Glebe was amalgamated into the City of Sydney in 1949 and lost its municipal status. As a consequence, Anzac Day services were not held at the memorial for the next 45 years.

The Glebe War Memorial in recent decades

Our memorial was badly vandalised in the late 1980s when the busts of the digger and sailor were stolen, the angel decapitated, and the nameplate graffitied. In 1991, a Diggers Memorial committee comprised of Dr Bill Nelson, Rev Hugh Scott and Max Solling was formed. A Restoration Appeal was launched on 17 October 1992 by Leichhardt Mayor Larry Hand and Major General Sharp spoke in support.

The task of overseeing the first and second stages of the restoration work, which took place between 1992 and 1997, was overseen by the Diggers Memorial Committee and the work was carried out by Traditional Stonemasonry Co Pty Ltd. The total cost of the memorial’s restoration was $42,680 achieved with a $19,800 NSW Heritage grant and community contributions of $22,880.

The first Glebe Anzac Day service to be held since 1948 was at a partially-restored memorial in 1994. The address was delivered by Major MJ Miller from the Sydney University Regiment.

More extensive conservation of the Glebe War Memorial was undertaken by the City of Sydney between 2013 and 2015. This included new hand-carved busts of the soldier and sailor, the Italian marble angel and the missing bronze Victoria Cross at the top of the shrine. (Watch the three-minute video about the restoration including the clever process by which the Victoria Cross was reproduced.) The additional conservation work was part of a program to conserve historic war monuments to mark the Gallipoli centenary. The program also included eight other memorials, the Martin Place Cenotaph and the Archibald Fountain. The cost of this restoration work to the Glebe War Memorial was about $250,000.

Join the conversation on Facebook.