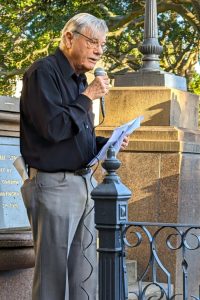

By Max Solling, Bulletin 4/2024, June

This morning, I would like to share thoughts on memorials, Indigenous Australians in the First Australian Imperial Force (AIF) and the women of Glebe.

After 1918, when the war had become a past experience, local communities across Australia designed and built war memorials. No community was untouched by the loss of young men who had gone to war and did not return. The ‘war memorial movement’ manifested the grief and pride these communities experienced in the face of such loss. Civic committees created and funded most memorials, and these artefacts took many monumental forms. Ken Inglis and Jan Brazier’s Sacred Places (2008, 3rd edition) is a memorable reading of these Australian monuments and an evocation of the culture of the First World War.

War, remote initially, took on a sense of purpose with the Gallipoli landing on 25 April 1915. The women of Glebe quickly mobilised, engaging in door-to-door knocking for the Patriotic Fund, organising dances and euchre nights, knitting socks and other activities in aid of the Glebe branch of the Red Cross Fund, and organising local concerts for the Belgium Fund where Eva Rainford sang. At the same time, Sergeant Taylor, officer-in-charge of the local police, began a recruitment drive, and the Glebe Rifle Club, which conducted drills in Wentworth Park, was formed. Eight years later, in 1923, Glebe women participated in a moving pilgrimage to their cenotaph shrine, an event explored later.

War tore families apart, and nothing could have wholly reversed this tide of separation and loss. After receiving the awful news of death, people were overcome by grief, passing through stages of bereavement. Australian families were among the furthest removed from the main theatres of military operations. Approximately 60,000 of 330,000 Australians in the AIF were killed or died on active service, a casualty rate at or above that suffered by the British, French and German armies.

Indigenous Australians in the AIF

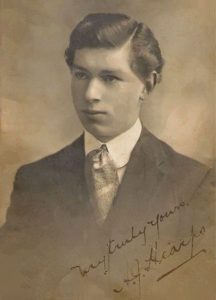

Alfred John Hearps, son of a Palawa man from Forth Tasmania, enlisted as a 19-year-old in the AIF in 1914. He was at the Gallipoli landing and as a second lieutenant became the first Indigenous Australian to be commissioned. Hearps was killed on 19 August 1916 on the Somme. With no known grave his name appears on the Villers-Bretonneux memorial. According to recent research, somewhere between 1,000 and 1,500 Indigenous Australians donned the khaki. They defied racist restrictions but on their return to civilian life were denied full citizenship rights. Yet Indigenous Australian soldiers shared a commonality of service and sacrifice made by all Australian soldiers. Once in the AIF they were treated as equals, paid the same as other soldiers and generally accepted without prejudice.

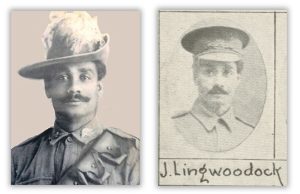

Leading the service on this year’s Anzac Day, Pastor Ray Minniecon, a Kabikabi and Gurang-Gurang man from Queensland, has dedicated his life to supporting members of the Stolen Generations of Aboriginal people. Ray has a strong connection with the defence forces; his grandfather James Lingwoodock (1895–1960), an excellent horseman like many stockmen, joined the 11th Light Horse in 1917. He was part of reinforcements known as the ‘Queensland Black Watch’ in the Jordan Valley: 28 of its 32 members were Indigenous. Ray’s two brothers, Sterling known as ‘Sonny’ and Phillip, served in the Vietnam War. Ray was a transport driver in the Citizen Military Forces (CMF).

Writing letters and keeping diaries helped soldiers cope with the chaos surrounding them at the front. Charles Tednee Blackman (1895–1966), an Indigenous farm hand from Childers near Bundaberg, enlisted in 1915 and was followed by elder brothers Thomas and Alfred. He survived two and a half years of the morass of trench warfare in France. Charles Blackman’s letters home reveal the sense of duty, fears of battle, pleasures of leave, camaraderie and esprit de corps with white comrades, and loneliness of being so far from home – common to all soldiers.

The War Memorial Movement

Families received news of the fate of AIF men, 12,000 miles from home at Gallipoli and in France, from clergy who were notified by official cable at an interval of about 10 to 14 days after the event. Their dead lay far away. The loss of so many on the other side of the world, without any possibility of a funeral, left an aching void in their lives. Australia’s response to the horrors of World War I following the Imperial government’s decision that there would be no repatriation of bodies was manifest in the proliferation of memorials across Australian landscapes.

In a population of more than four million people in 1915, the number of memorials in Australia is extraordinary – 516 in NSW and 1,445 across the country. A few were built during the war, but most were built in the decade following the Armistice.

War memorials near us in inner Sydney were popular subjects of postcards. Seeking out these ‘sites of memory’ helps us understand the complex impact of the First World War on our cultural history. A journey of discovery might start with the sculptures of English-born Gilbert Doble (1880–1974) who chose the symbolic woman instead of the fighting man at Pyrmont, Leichhardt and Marrickville. Doble created a winged female figure holding a shield – named ‘Peace’ – in a conspicuous place at Union Square, Pyrmont, and near Marrickville Town Hall, a bronze-winged female figure named ‘Winged Victory’. The Leichhardt monument, moved from near the Leichhardt Town Hall to Pioneers Memorial Park, is a tall tapering granite pedestal with a bronze female named ‘Peace’ with a wreath on her head. Doble was the first to employ a hammered bronze method to create these figures, cheaper than traditional casting.

Wives and mothers of soldiers chose a drinking fountain to be installed near a Woolloomooloo wharf ‘to commemorate the place of farewell’ where diggers boarded troopships heading to the European conflict. Another drinking fountain on a pedestal can be found at Loyalty Square Balmain; the sandstone pedestal supports tablets and a prominent mounted light on an iron frame. Unveiled in 1916, this monument records the names of men who died at Gallipoli and features the words ‘Peace, Honour, Empire and Liberty’. And at Redfern Park, a magnificent granite monument was installed, adorned with two striking carved marble figures – an Australian soldier and a young woman holding a scroll.

The Cenotaph in Martin Place is the centre point of Sydney’s Anzac Day, with its bronze soldier and sailor by the doyen of native-born sculptors of statues, Bertram Mackennal (1863–1931). Marchers on Anzac Day moved in impressive columns of twelve down Martin Place, parted into sixes after Castlereagh Street, and as they reached Pitt Street, removed hats, held them over hearts, and turned their heads towards the wreath-laden Cenotaph. This monument provoked the spontaneous creation of a new ritual, the dawn service, commemorating that dawn of 1915, at which the landing at Gallipoli became a visual metaphor for the beginning of Australia’s nationhood.

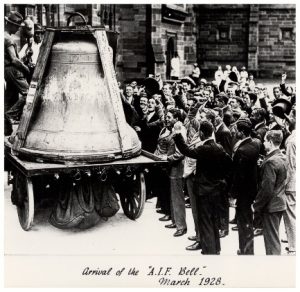

A major crowd-funded project, the Sydney University War Memorial Carillon, opened on Anzac Day 1928. Two bronze memorial walls were dedicated to the 197 Sydney University undergraduates, graduates and staff who died during the First World War. The Carillon’s 49 bells, cast in England, were carried by horse and cart from Wolloomoolloo Bay wharf to the University’s clock tower and installed for £17,380. The Carillon’s four-and-a-half tonne great bell was dedicated to the AIF and named the ‘AIF Bell’.

Glebe’s Kiama trachyte and marble mausoleum, 102 years old on this year’s Anzac Day, was designed by architect, anti-conscriptionist and Glebe alderman William Martin. A very Australian monument, neither the Empire nor Britain is represented in the mausoleum. Stonemason Alessandro Casagrande, who emigrated from the Veneto region in Italy, sculpted the busts of the soldier, sailor and Carrara marble angel that guard those symbolically resting in the mausoleum. Under the guardian angel is a simple and understated dedication: ‘Erected by Glebe Residents in Memory of the Glorious Dead’. An entirely local initiative, residents paid £2,964 for its creation.

Annandale’s monument at Hinsby Park fronting Johnston Street is a unique type of shrine. A four-metre high Bowral Trachyte obelisk and plot of remembrance embracing an ‘ersatz grave’ representing their dead is flanked by seating curved forward in a quadrant plan. The obelisk was the creation of stonemason Frederico Gagliardi.

Camperdown Sailors and Sailors League lost their Council in 1909 but ensured their dead were represented. Located in Camperdown Park, the bluestone monument is surmounted by a marble figure of a soldier with a rifle. And tram workers at Rozelle Tramsheds who had died in WWI were represented by the figure of a soldier holding a rifle with a bayonet, cast in white cement. ‘Erected by their Comrades’ in 1916, this sculpture by Edwin McGowan is believed to be the first to depict a digger at a workplace.

All these physical, emotional and artistic artefacts testify to the catastrophic character of WWI. Throughout the war, pageants, processions and celebrations were regular features of the Glebe landscape. Processions along the suburb’s main artery were brightened by bands, banners and sashes. Glebe’s para-military organisations encouraged a sense of participation. A September 1916 Daily Telegraph article titled ‘Glebe Fighters Home’ recounts a ‘street procession and carnival’ at which the Glebe Cadet Band and the Police Band, flanked by local councillors, led a rowdy public welcome to returned men travelling in decorated cars. Two weeks later, a carnival organised by the Glebe Local Distress Society greeted more returned men.

As casualty lists grew, an outpouring of grief, tears, agony and pain by countless Glebe residents filled newspapers’ in memoriams. Declining enlistments concerned Prime Minister Hughes, who had promised Britain a quota of recruits he could not fill. The six o’clock closing of pubs – the outcome of a referendum held on 10 June 1916 – limited workers’ access to their temple. Conscription campaigns in 1916 and 1917, together with cost of living increases, raised discontent amongst the citizenry that lasted at least a generation: the volunteer against the ‘shirker’, the conscriptionist against the anti-conscription, and although sectarianism was not created by war, the Protestant against the Catholic.

Birth of the Glebe War Memorial

A meeting chaired by Glebe Mayor Finlay Munro on 4 April 1919 agreed to create a memorial to Glebe soldiers who died. A six-member committee of Council employees and residents, led by Tom Keegan (president), Tom Glasscock (town clerk) and Bill Brown (honorary secretary), began compiling names of those who died and opened a bank account for monies raised to pay for a cenotaph shrine. Governor General Forster unveiled the Glebe memorial on Anzac Day 1922, and Rachel Forster unveiled the busts of the soldier and sailor on either side of the central shrine. This formal ceremonial occasion was described by Lord Forster as a ‘day of triumph and of glory, rather than a day of mourning’.

Glebe women grasped the opportunity on Anzac Day 1923 to make a profound statement of grief and pride for their collective loss. It was their special day, taking the form of a pilgrimage of mothers, widows and sisters to the shrine, all dressed in black and wearing black hats, reflecting the sombre mood that pervaded the war and early post-war years. And they turned up en masse and, together with other grieving folk, crushed around the shrine. One can only imagine these poignant scenes, charged with high emotion and solemnity. Among the pilgrims were Rachel Curtis, Susan Maltby, Margaret Cotter, Ellen Sharpe, Margaret Faerber and Emma Neaves, Glebe mothers who each had lost two sons.

We will never know how the bereaved mourned and what became of them, but we do know the widow’s pension they received – about ten shillings a week – was only one-quarter of the average weekly wage, a level of benefit less than that paid in Britain and France.

The pilgrimage commenced with memorial secretary Bill Brown reading out, in alphabetical order, the names of each fallen soldier inscribed in gold on the mausoleum’s marble nameplate. On hearing their son’s or husband’s name, a Glebe woman stepped forward to lay a wreath or sheaf of flowers. With all 174 names called, the ceremony was a prolonged affair – and left a searing impression.

Many bereaved women would return on the anniversaries of death or birth to spend time at the shrine. On these intensely personal occasions, passing local pedestrians observed women standing quietly in front of the shrine, head bowed in quiet contemplation. They could not see their faces. They did not want to.

Recent history of the Glebe War Memorial

For the record, I’d like to explain what has happened at the Diggers Memorial since 1992. Anzac Day services were conducted here from 1922 to 1948. Glebe was amalgamated into the City of Sydney in 1949 and lost its municipal status. Consequently, Anzac Day services were not held here for the next 45 years.

Our memorial was badly vandalised in the late 1980s when the busts of the digger and sailor were stolen, the angel decapitated, and the nameplate graffitied. In 1991, a Diggers Memorial committee was formed, which was comprised of Dr Bill Nelson, Rev. Hugh Scott and me. A Restoration Appeal was launched on 17 October 1992 by Leichhardt Mayor Larry Hand, where Major General Sharp spoke in support.

The task of overseeing the first and second stages of the restoration work, which took place between 1992 and 1997, was overseen by the Diggers’ Memorial Committee and the work was carried out by Traditional Stonemasonry Co Pty Ltd. The total cost of the memorial’s restoration was $42,680, achieved with a $19,800 NSW Heritage grant and community contributions of $22,880. The first Glebe Anzac Day service since 1948 was held at a partially restored memorial in 1994. The address was delivered by Major MJ Miller from the Sydney University Regiment.

More extensive conservation of the Glebe War Memorial was undertaken by the City of Sydney between 2013 and 2015. This included new hand-carved busts of the soldier and sailor, the Italian marble angel and the missing bronze Victoria Cross at the shrine’s top. The additional conservation work was part of a program to conserve historic war monuments to mark the Gallipoli centenary. The program included eight other memorials, the Martin Place Cenotaph and the Archibald Fountain. The cost of this restoration work to the Glebe War Memorial was about $250,000.

Rob McLean, 30 years piping for Glebe’s Anzac Day

A constant figure at annual services here since 1994 has been our wonderful piper Rob McLean who plays the lament. Rob’s father, John McLean, was born at Kinlochleven, Argyllshire, in the Scottish Highlands and emigrated to Sydney with his parents in 1929.

After Rob left school in 1968, he joined the St George–Sutherland Pipe Band, after which he joined the Sydney University Regiment Army Reserve, where he served for 32 years. We were lucky enough to get Rob in 1994 through his involvement in the Sydney University Regiment. Rob has played at Burwood’s Anzac Day dawn service for over thirty years, leaving Burwood by 7 am to get to Glebe for our 7:30 service. After finishing at Glebe, Rob heads into the city to join the Pipers and play at the march.

Sources: Ken Inglis and Jan Brazier (2008) Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape (3rd edition); NSW War Memorials Register; National Library of Australia (Trove)

There are no comments yet. Please leave yours.