By Virginia Simpson-Young, Bulletin 4/2023, June 2023

If you missed this event, you missed an inspiring and fascinating deep dive into the research collaboration – funded by a City of Sydney Innovation and Ideas grant – between the Glebe Society and Professor Dieter Hochuli’s Integrative Ecology group at the University of Sydney. But fear not; below you’ll find links to each speaker’s presentation, which I’m sure you’ll find as interesting as we did on the day.

Andrew Wood, convenor of the Glebe Society’s Blue Wren Subcommittee, expected a modest turnout to this event, but the rush on tickets surely caused him to wonder whether the Harold Park Community Hall was big enough to accommodate all-comers. Fortunately, it was, and around 90-100 people attended on the afternoon of Sunday, 7 May, to hear all about this significant research collaboration.

Mark Stapleton, Glebe Society Vice-President, began the meeting by acknowledging the traditional owners of the land on which we met and the adjacent land, now known as The Hill. Mark then introduced Lord Mayor Clover Moore, who officially opened the event.

Ms Moore explained that the Council’s Innovation and Ideas Grants program supports “innovative projects that address local and global issues and contribute to a sustainable city, thriving economy, vibrant communities and cultural life”. She added that the Glebe’s Hill collaboration was “a great community-led initiative, underpinned by a robust partnership” between the Glebe Society and the University of Sydney and that she expected Glebe’s Hill to become part of the Johnstons Creek Parklands in due course.

Also from the City of Sydney was James Macnamara who spoke about the municipality’s biodiversity potentials. In his role as the City’s Urban Ecology Coordinator, James looks after “all thing’s native animals and native plants, except for trees”. He saw the Glebe’s Hill project as “an important first step” in promoting biodiversity within the City and that before the Council advances “too far with these efforts, it is important to identify the existing ecology of an area – to know what we have and what we are missing”. His role in the Glebe’s Hill project is “to support the Glebe Society in the [project’s] delivery”. James spoke about how the project can help the City achieve its goals to “increase green cover to 40 per cent across the council, with a minimum of 27 per cent tree canopy by 2050”.

Glebe’s resident historian, Max Solling, gave a potted post-colonisation history of The Hill, describing its inauspicious beginnings as a rubbish heap – the cause of the site’s contamination that has required its being fenced off to prevent public access. At some point in the post-colonisation history of municipal waste, Glebe Council thought it would be an excellent idea to dump residents’ rubbish in the ocean rather than on what was to become Jubilee Park and The Hill. Audible gasps could be heard from the audience when Max told us that Glebe municipality was the last to stop punting rubbish out to sea, which they did in July 1933. Undoubtedly, Bondi beach-goers were relieved to no longer share the breakers with the detritus that often made its way back to shore.

Glebe Council belatedly (and arguably) saw the light and built an incinerator in Forsyth St, which, while substantially reducing the need to find a place to locate garbage, merely converted residents’ waste from a solid contaminant to a gaseous one. Max concluded his presentation by noting that the Board of Health had declared the area now known as Harold Park unfit for human habitation and that “no buildings of any kind were to be built there”.

With Max’s rather depressing history of The Hill still ringing in our ears, Andrew Wood’s presentation reassured that the Glebe’s Hill project would go some way towards undoing the sins of our municipal fathers by laying the groundwork for rehabilitating the land so ignominiously formed from residential rubbish.

Andrew reminded us that 23 years ago, the Glebe Society became aware that our suburb’s superb fairy-wrens and other small bird populations were declining. A dedicated band of residents was galvanised into a long-term campaign to preserve and restore the habitat for the blue wren and other small birds. Recently, the Blue Wren Subcommittee began to wonder whether The Hill – 0.6 Ha of isolated and protected land – was good habitat for small birds and other native fauna and flora. If The Hill’s habitat were to be enhanced, a baseline was needed as a jumping-off point for ecological restoration. Obtaining that baseline is one of the aims of the Glebe’s Hill research project.

The Hill is currently subject to an unresolved Aboriginal Land Claim. As time progresses, the management of Glebe’s Hill could be transferred to our Indigenous colleagues. Whatever the outcome, the Society hopes that the findings of this project can help inform any potential use of the site and whether, in the longer term, it could become a protected nature refuge with controlled public access. Perhaps, in the future, The Hill could be given an Aboriginal name in recognition of its traditional owners and their stories about Glebe’s history.

Having heard from Andrew about the rationale for The Hill project, we turned to the main event: the presentation by Professor Dieter Hochuli from the Integrative Ecology Group in the University of Sydney’s School of Life and Environmental Sciences. Dieter is the lead researcher on the Glebe’s Hill project.

If I were to say that Dieter’s presentation merely described the methods to be used by his researchers, I would be doing it an injustice. Dieter did this, but integrated it with key ecology concepts and what is known about ecology in cities, particularly in the city of Sydney. In his presentation, Biodiversity in Glebe’s Hill – benchmarks and possibilities, Dieter began by posing, ‘What does a weed-infested and degraded space contribute to ecology in cities?’ He answered this question by considering Sydney’s ‘natural legacy’ as ecosystems supporting native plants and animals – and us.

We heard about research by Dieter’s team and others showing how various creatures use Sydney’s fragmented natural environment to live their best lives. Included were the insectivorous bats, the superb fairy wren and everyone’s favourite bird, the brush turkey. Dieter described the methods used by researchers to locate these animals and map their peregrinations, often over surprisingly large distances. After this crash course in ecological methods, we heard about how these methods will be applied in the Glebe’s Hill project.

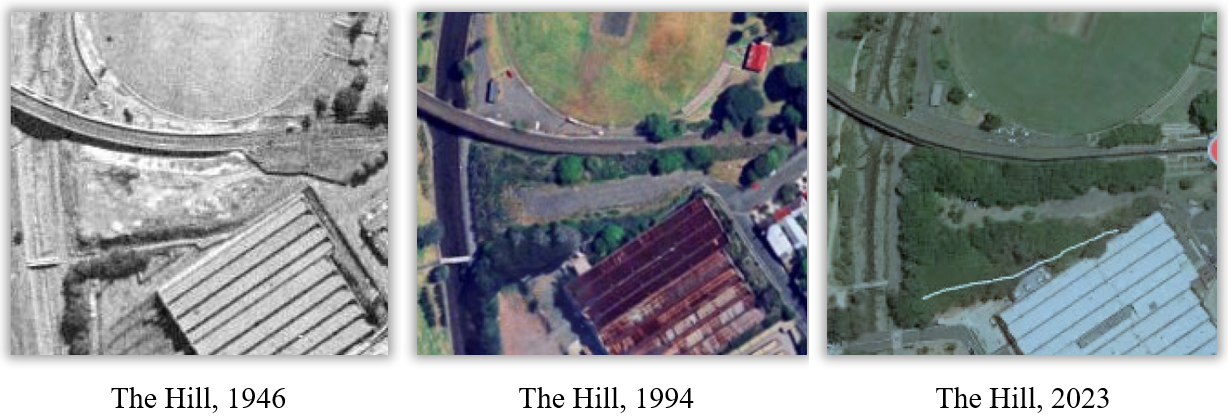

The Glebe’s Hill project aims to identify The Hill’s environmental history and the extent to which some ecological restoration has already occurred, even if only by accident. This latter process was demonstrated in a series of photos of The Hill taken between 1943 and 2023 (see image below). We saw The Hill, once denuded of vegetation, gradually growing a crop of large, mature trees. The project also aims to identify “what’s there and what could be there”. To address ‘what’s there’, the researchers will conduct surveys of The Hill by systematically dividing it into equal-sized plots and using camera traps, acoustic monitors, remote sensing and in-person surveys to identify communities of plants and animals and the habitat traits that may contribute to their success in The Hill’s degraded environment. It was great to hear also that fledgling ecologists will undertake some of this work for their honour’s year projects.

Ultimately, the Glebe’s Hill project is expected to add to our understanding of “why high quality small, isolated greenspaces matter” in cities. Dieter’s love for his field – the ecology of cities – was palpable, and I’m sure I wasn’t alone in being inspired by his enthusiasm. While I could have listened to Dieter all day, he concluded, and a short time remained for audience questions. Fortunately, Dieter was available after the session to answer other questions one-on-one.

After the session, most attendees stayed for a chat over an afternoon tea provided by members of the Blue Wren Subcommittee. No doubt we can look forward to future Bulletins providing updates on the Glebe’s Hill project.

There are no comments yet. Please leave yours.