Book review by Richard Cashman, Bulletin 7/2024, September

Greyhound racing is one of the pariahs of Australian sport. In contrast to the allied sports of horseracing and trotting, greyhounds have attracted more than their share of criticism mainly from conservative politicians and Protestant clergy. The Baird (Liberal Party) New South Wales Government even banned the greyhound racing industry in July 2016 because of alleged animal cruelty. In 1927, Thomas Bavin’s conservative government had earlier sought to scuttle tin-hare racing in 1927 when it prohibited betting, an integral part of the sport, after sunset. The pejorative phrase, ‘going to the dogs’, has been levelled at greyhound spectators.

Greyhound racing has been largely ignored by sports historians, who have preferred to write on the more glamorous sports of horseracing and trotting. Greyhound racing does not feature in the Cambridge History of Australian Sport and gains only brief mentions in the Oxford Companion to Australian Sport.

Sports historians have not interrogated this prominent and complex sport, which has two distinctive strands. It began as the genteel rural sport of coursing, where two dogs raced after a live hare. Coursing, which operated under the patronage of local gentry, permitted betting. Technology, in the form of the electric hare, imported from America in 1927, transformed the sport into a more proletarian and urban event. Large crowds attended night meetings in some of the more working-class suburbs of Sydney. Greyhound racing was a unique sport in that working class men could participate [in] it as owners, breeders, trainers and punters. J.T. Lang, New South Wales Labor Premier at the time of the Great Depression, was a supporter of greyhound racing, declaring that a greyhound was the working man’s horse. Dogs were more affordable than horses, they could be accommodated in a suburban backyard and exercised around the neighbourhood. Australia was the third largest producer of dogs in 2001 with an estimated 20,500 greyhounds bred in this country after the United States (32,000) and Ireland (23,000).

Max Solling and John Tracey have produced the first major study of greyhound racing. The book raises many fascinating issues. Coursing was extolled by the Referee in the 1890s as a sport for gentlemen. It is ironic that officials Richard Coombes and E. S. Marks, who promoted the virtues of amateurism, were prominent in the administration of coursing even though gambling was involved. Coombes was president of the NSW National Coursing Association for 27 years and helped set up a national body of which he was president … for a decade. He also trained greyhounds. Coombes saw nothing contradictory in his support of coursing and argued that ‘there were no gambling evils in coursing’ because only small bets were laid.

After tin-hare racing was introduced from America, the sport moved from open fields to circular tracks in the poorer sections of Sydney. Night meetings proved very attractive and crowds of up to 30,000 who attended were served by 150 to 200 bookies. It was cheaper to attend and bet on the dogs than it was at horseracing or trotting meetings.

Tin-hare racing also took off in country towns where it established deep roots in the community. ‘The greyhound track’, the authors wrote, became ‘a crucial part of the town’s social fabric, reliant on voluntary help … just as the Rural Fire Service is another integral part of rural self help’. Once the infrastructure had been set up for the mechanical hare, it was cheaper to race dogs than horses.

Solling and Tracey include a number of thematic chapters on class and the expanding greyhound industry. The authors take issue with those historians who contend that greyhound racing was exclusively working class. While 95 per cent of greyhound owners were small owner trainers, ‘hobby trainers’ who did not have dogs that were good enough to compete in the major venues, the sport was in fact run by middle-class entrepreneurs, organisers, investors and trainers. Middle-class support enhanced the respectability of the sport. Prominent Sydney retailer Anthony Hordern was an active member of the Greyhound Racing Club in 1932.

Greyhound racing survived the attempt by the Baird Government to shut the sport down in July 2016. The announcement brought an immediate outcry, particularly from the bush, and a wide coalition opposed the move. It included the members of the Labor Party, Nationals from the bush – three crossing the floor when the Bill was proposed – the Rev. Fred Nile and supporters of the greyhound industry. Baird was forced to back down only three months after announcing the ban.

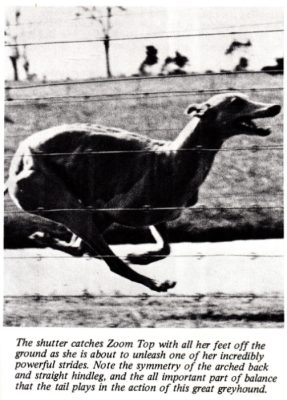

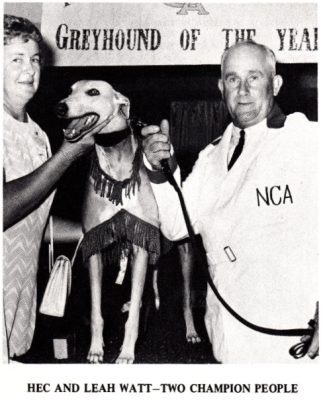

Going to the Dogs is enhanced with a superb collection of photographs, courtesy of passionate and committed greyhound breeders and trainers Don and Christine McKenzie, who have built up an outstanding collection of greyhound photographs dating from 1927. There is an affectionate photograph, opposite the book title page, of an owner reclining in his backyard with arm around his dog. The plethora of photographs in this book demonstrate that the sport was primarily one for men though there are occasional glimpses of women and children involved in the sport. There are images of women at a Ladies Day coursing meeting in Victoria in 1880. Thomas Bavin launched a scathing attack in 1931 on women and children ‘gambling a few shillings’ on greyhound courses. The only image that features a female as an owner was of Leah Watt who trained a champion dog, Zoom Top with her husband Hec. However, there are references to other greyhound women in the text: Leonie Brown owned 13 greyhounds in the Southern Highlands, Maree Callaghan was a Cessnock owner for 35 years, and Doreen and Kevin Drynan had 35 greyhounds in their Llandilo kennel in an outer suburb of Sydney. There is a story here for further investigation – how rural women became involved in greyhounds.

Solling and Tracey have produced a well-researched and impressive book on one of the neglected sports of the country. It is a valuable addition to the sports history library. Reading this volume makes one wonder why sports historians privilege some sports over others and how this preference is justified. The authors demonstrate that there is much to be gained by a thorough interrogation of what many have regarded as a sport on the margins of respectability.

This review appeared in the journal Sporting Traditions in June 2023. Cashman, who is Adjunct Professor in Management at UTS, has written extensively on sport in Australia, including two histories: Paradise of Sport (1995) and Sport in the National Imagination (2003). He edited the Oxford Companion to Australian Sport and is a former president of the Australian Society for Sports History.

There are no comments yet. Please leave yours.