by Neil Macindoe, Planning Convenor, June 2010. Updated.

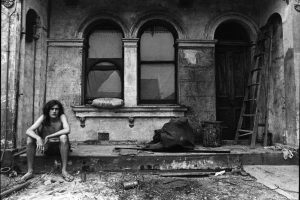

Fifty years ago, the visitor to Glebe would have seen a very different suburb. The waterfront was cluttered with industrial sites, mainly belonging to the timber industry. Sometimes it would be possible to walk across Rozelle Bay, it was so choked with floating logs. There was just one small waterfront park, Marine Reserve, at the end of Glebe Point Road. White Bay Power Station belched out fumes that blackened washing as soon as it was hung out. Scattered throughout residential areas were a wide range of small factories, including foundries, soap and paint works, and many other noxious and polluting trades. Most dwellings had not seen a coat of paint in living memory – many of them were decayed, and their facades and balconies obscured by fibro and plywood. A considerable number were owned by slum landlords, who divided them into many small flats populated by transient residents.

Rediscovering Glebe

It was a story repeated throughout the inner city. Expanding railways and cheaper cars brought the Australian dream of a new house with all mod cons on a quarter acre block within reach of the majority, and home ownership boomed in the suburbs. Inner areas such as Glebe were left to those who couldn’t afford to leave, or had to find somewhere cheap. In those days it was rare to find someone who regarded Glebe as other than a slum, including the people who lived there. It was assumed that one day the whole suburb would be demolished, and when two new freeways were proposed to drive through Glebe, many people thought it progress. Similarly, the increasing tendency to knock down old houses (especially on large corner blocks) and replace them with cheap three or four storey walkups seemed like the inevitable march of the modern world.

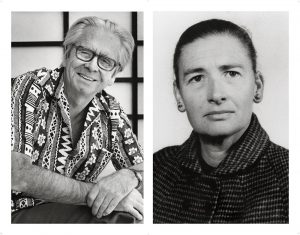

It was not easy to see the beauty obscured by blight, accretion and neglect, but this was the particular talent of Kate and Bernard Smith and the other founder-members of The Glebe Society. In this they were supported by a change in public mood, heralded by the foundation of the National Trust and many local resident action groups that, for the first time, recognized the value of the past and resisted its indiscriminate and wholesale destruction. In their imaginations the fine craftsmanship and urban planning of the Victorians blazed into life again like the burnishing of tarnished brass. In the close bonds of the local residents they recognized the value of established, mutually supportive communities. From this moment, the heritage of that community and its future development became inextricably linked.

The great energy shown by the Society in its early years is a consequence of facing so many threats. Both freeways and developers threatened demolition. The freeways were stopped with one campaign, but a new town plan was needed to cope with developers, not just to prevent unnecessary demolitions, but to control those industrial sites, and as they inevitably became redundant, to ensure their best future use.

Parks for the People

The total occupation of the waterfront by industry raised a wonderful possibility: perhaps it would be possible to secure continuous public access to the foreshore. This possibility, after 30 years of effort, will be realised in 2014 with the completion of the final section of the foreshore walk. It is one of the Society’s great triumphs, and is a major contribution to Sydney Harbour, as it links with a proposal for continuous waterfront access as far as Garden Island. This campaign fitted neatly with the need to remove polluting industries and increase high quality open space.

The Society also saw the possibility of linking the waterfront parks to those following original watercourses inland. As a result of community campaigns Wentworth Park, built on reclaimed land in the late 19th century and once second only to Centennial Park, has once more become desirable public open space, and the Orphan School Creek corridor in Forest Lodge has been regenerated as natural bushland. Rezoning industrial land on the waterfront does have a cost. If the land cannot be bought or obtained outright, it can only become park by allowing some residential development.

The last of the waterfront industrial sites, the Australand site extending between Ferry Road and Forsyth Street, has now been residentially redeveloped. Fortunately, it was possible to combine the new open space with Council land, so one third is now waterfront park. Also, the heritage-listed Walter Burley Griffin incinerator, including Griffin’s landscaping, has been restored.

Saving the Glebe Estate

Another early threat was the proposed sale of the Church of England lands that form part of the original land grant that gave Glebe its name. The Society provided the information and impetus that enabled the Whitlam Government to purchase all 740 dwellings, transferred to the NSW Department of Housing in 1984.

By saving the Glebe Estate the Society preserved both the community, many of whom had lived in Glebe for generations, and a rare example of housing and planning from the Gold Rush period onward.

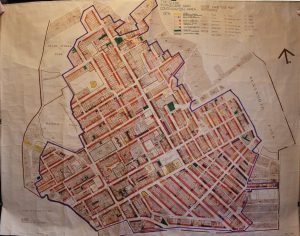

By 1974, the Society had sufficiently established the value of the suburb for Glebe to be declared an Urban Conservation Area. Also in 1974 a reforming Leichhardt Council drew up a promising new Planning Scheme, but the next Council rescinded it in 1976. However, by 1983 a new Town Plan (known as Local Environment Plan No 20) had been gazetted that recognized Glebe as a Conservation Area and listed all buildings recorded by The National Trust as Items of Environmental Heritage. The change in public mood can be gauged by a change of State Government that put an end to the expressway plans and passed both a Heritage Act (1977) and the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act (1978), establishing a Court to hear planning appeals. LEP 20 also set a maximum density for new residential development (175 persons per hectare) that in normal circumstances limited it to two storeys (with rooms in the roof) with parking underground. Leichhardt Council also adopted a Development Control Plan (No 1) establishing general characteristics of design, form and height, including detailed recommendations for each distinctive area.

The spirit of these changes can best be seen on the Glebe Estate, where a young and talented Department of Housing team combined social and heritage objectives. The houses received new bathrooms and kitchens, a simple improvement that at one stroke has greatly extended the life of houses throughout the inner city. Where lot sizes permitted, extensions at the rear of dwellings made them suitable for families, and for the first time the decline in Glebe’s population was reversed. The wave of young children and teenagers revitalized the local schools. The team took advantage of vacant sites and derelict houses to create purpose-designed housing for seniors and other infill dwellings employing transitional architectural styles that blended with traditional housing. Good examples can be seen in Darling, Catherine and Glebe Streets.

A Slum No More

The renovation of the Glebe Estate paralleled the revival of interest in the four-fifths of Glebe which was privately owned. It is now common for Glebe houses to have their most prominent features restored, including external iron lace and paint, and interior ceiling roses and cornices. Modernisation is typically limited to bathrooms and kitchens, with perhaps the rear opened out to create sunrooms and decks.

The revival of interest in Victorian urban housing has had a variety of consequences. It has raised the cost of such housing beyond the wildest imaginings of its former inhabitants, for whom it was a cheap refuge. Despite this, Glebe remains a predominantly rental suburb, with over 60% of private dwellings being rented according to the 2011 census. Even so, the number of students, for example, has declined drastically. Generally, social divisions have been sharpened. Almost the whole of Glebe has been restored. Its public areas, notably its library and waterfront parkland, have been extended and transformed.

Unfortunately, rising prices and the higher densities achievable in Victorian areas have also made Glebe a target for developers, car ownership has increased, and house occupancy rates have declined. New routes and more frequent buses have improved public transport, but the most dramatic change is the Glebe Society-initiated conversion of the spectacularly-engineered goods line which served Darling Harbour to light rail. The extensions of the light rail westward to Dulwich Hill, further along the goods line, and eastward along George Street to Circular Quay, were approved by the State Government in 2012-13.

Future Development

Most problematic development in recent years has been of two kinds, both the result of increasing property values. Firstly, those buying houses in Glebe are much richer, and are not necessarily attached to its heritage. Hence, attempts to extend and modify existing houses are more common (the Balmain syndrome). Secondly, developers pore over aerial photographs trying to identify and large backyards or non-heritage buildings so they can pop up a few townhouses (the Leichhardt syndrome).

It was with these challenges in mind that Leichhardt Council introduced Town Plan 2000, which has stricter environmental controls, reflecting concern about overdevelopment and the need to make new building sustainable. At the same time development control plans tightened up requirements in particular suburbs.

When Glebe became part of the City of Sydney in May, 2003, the City continued to apply Town Plan 2000, but since 2012 a new City Plan has been in place covering the whole of the local government area. The fringes of Glebe, which are affected by development in adjacent suburbs, remain areas of concern, as do the foreshore of the Bays opposite Glebe which have a large impact on Glebe but are generally outside local government control.

Problem sites

There are also a number of sites that, for a variety of reasons, resisted solutions for a long time. Probably the best known of these is The Abbey site, 156-60 Bridge Road. So far one heritage building on the site, Reussdale, has been renovated as a residence and the church is being restored for commercial use. The cottage called Hamilton is to be rebuilt as a duplex, and there will be seven townhouses along the rear of the site.

Bellevue, in Blackwattle Bay Park, has been restored and a cafe. The restored Walter Burley Griffin Incinerator on the Australand/Fletchers site (see above) is available for community use. Both are Council-owned heritage buildings.

At present the major development site is Harold Park. This will result in 1250 units in blocks from five to eight storeys, with building occurring for up to eight years. One third of the site (3.8 ha) is to be a new park and the former tramsheds are to be restored as a commercial precinct for the new development, with 500 square meters of community space. The site is very large and it will be some years before development is completed.

Development pressure is not unique to Glebe, but dealing with each case requires a great deal of effort, often over decades. It is often said the threats to Glebe are never-ending, and this is a major factor in the resilience of The Glebe Society when so many other resident groups have vanished. Certainly The Society’s role is never less than challenging, and your support is always valuable.

There are no comments yet. Please leave yours.