Ian Stephenson, Bulletin 5/2022, July 2022

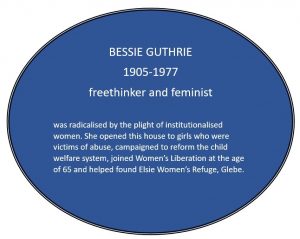

In September last year the NSW Government called for communities to nominate places linked to notable personalities and events for recognition as part of the NSW Blue Plaques program. The Glebe Society made a number of nominations. The fifth site nominated by the Society is 97 Derwent St Glebe.

Bessie Guthrie (1905-1977), designer, publisher, feminist and campaigner for children’s rights grew up, and lived until her death, at 97 Derwent St, Glebe.

From 1921 she attended classes at Technical College in interior design. Moving in bohemian circles, she became friendly with Hal Missingham, Kenneth Slessor and Dulcie Deamer. She wrote about design for the Australian Woman’s Mirror in the late 1930s.

In 1939 she founded Viking Press which focussed on poetry and anti-war tracts. During the war, she was head draughtswoman at De Havilland Aircraft Pty Limited’s experimental gliders factory. At the end of the war, she wrote talks on Plans for Women in the Post-War World (broadcast on radio), and organised training films directed at women dismissed from industry to make way for returning servicemen.

In the 1950s, she opened her house to young girls who were the victims of domestic violence, abuse, homelessness and the welfare system. Bessie became a crusader for children’s rights against the State child-welfare system. She researched every aspect of the Children’s Court, the welfare home system, Church homes and compiled case histories. She bombarded bureaucrats, journalists and politicians with letters demanding changes. She ran what amounted to a private halfway house at 97 Derwent St.

She had some success following the 1961 riots at Parramatta Girls’ Training School, obtaining a public inquiry. The government, however, established a maximum-security children’s prison at Hay as the ultimate punishment for rebellious girls: where enforced silence, shaved heads, solitary confinement and daily humiliations prevailed.

She broadened her research to include the institutionalised abuse of females, from babies charged with being ‘abandoned’ to homeless elderly women. A pattern of denial, evasiveness and misogyny emerged.

In 1970 she joined the Women’s Liberation Movement in Glebe. She helped produce their newspaper, Mejane, which published much of her research. She worked on mass protests outside Bidura Girls’ Home, Glebe, and Parramatta Girls’ Training School. She persuaded the television journalist Peter Manning to produce a full-length documentary, based on her research. The institution at Hay was closed in 1975. Her campaigns also led to the end of compulsory virginity-testing of girls charged by the Children’s Court and to the abolition of the charge of ‘exposure to moral danger’.

In 1974 with Anne Summers, Guthrie squatted in two adjoining houses in Glebe to found Elsie Women’s Refuge Night Shelter. In the 1977 Anzac Day campaign to draw attention to women raped in wars, Bessie made the decisive breach at the Cenotaph, pushing aside policemen and allowing groups of women to break police lines.

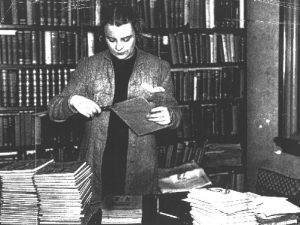

She was a radical freethinker, feminist, storyteller, bibliophile, sleuth, gourmet and lover of shopping and cafés. Bessie died on 17 December 1977 at Glebe.

Her funeral began as a street meeting outside her home. The procession, led by women on motorbikes, with streamers, banners and horn-honking, was stopped on Gladesville Bridge by police who refused to believe it was a ‘real’ funeral!

Note: This account of Bessie Guthrie’s life is an edited version of Suzanne Bellamy’s entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography.

There are no comments yet. Please leave yours.