by Lyn Collingwood, from Bulletin 7/2021, September 2021

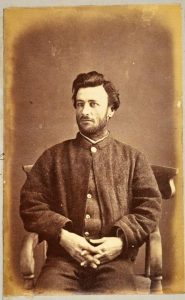

When Robert Fitzgerald Nichols (aka George Robert Nichols) was hanged for murder, details about his parents, spouse and children were not publicly divulged, and there was gossip about his paternity. Some supposed he was the adopted natural son of a man named Bobby Fitzgerald. But his respectable relatives knew who Nichols was and were desperate to distance themselves. Notices appeared in the Press, denying that he was a son of deceased master mariner Isaac David Nichols ‘and has never been recognised as such by any members of that gentleman’s family’.

The truth was that the killer was Isaac David Nichols’ illegitimate son and a descendant of two convicts who prospered. The first Isaac Nichols (1770-1819) was Robert Fitzgerald Nichol’s grandfather and the colony’s first Postmaster General. This Isaac Nichols married the daughter of Esther Abrahams, Rosanna Abrahams. Esther Abrahams married Lieutenant George Johnston of Annandale fame.

During the 1860s, Robert Fitzgerald Nichols, his father Isaac, and his paternal uncle Charles Hamilton Nichols lived on Glebe Point Rd.

Robert Fitzgerald Nichols was born in London on 28 August 1838, four months after his mother Catherine Adelaide McCrone had embarked from Sydney on the Achilles with Isaac David Nichols. In October 1839, Isaac Nichols returned to Australia as master on the maiden voyage of the Australasian Packet, an English clipper converted to a coastal steamer. The cabin passengers included French missionaries bound for New Zealand. It is likely that Catherine McCrone and the baby were also on board. The boy was baptised at St James on 13 January 1841. He was brought up by his father and attended Sydney College, Hyde Park. The fate of his mother, Catherine McCrone, is unknown.

Although a shrewd businessman, Isaac Nichols had been sentenced in 1836 for conspiracy to defraud creditors. He was released from Newcastle Gaol a year later, after which he formed a relationship with Catherine McCrone. With his legal wife Sarah née Hutchinson, he already had three children: William Charles (baptised 1830, died of delirium tremens in 1857), Sarah Martha (baptised 1832, died 1941) and George Robert, who was baptised in 1836 but whose fate is unknown. Sarah Nichols left her husband for Joseph Yeomans, an articled clerk to Isaac’s younger brother George Robert Nichols. (George Robert Nichols had two sons called George Robert Nichols; one died as a toddler in 1832, and the second died as an infant in 1838).

Robert Fitzgerald Nichols was first in trouble with the law at age 16 after returning to Sydney from a stint at sea. In court, he presented well, pleaded guilty to a charge of forgery and spent a few days in gaol. He was apprenticed to a butcher at Windsor but soon returned to shipboard life. He worked in a Custom House at Cadiz, was gaoled in London for obtaining money under false pretences, and in 1861 was back in Sydney. Although well-educated and fluent in several languages, he failed at one enterprise after another: shipbroker, commission agent, gold digger, illicit distiller, fisherman, ship lumper and railway porter.

Using his birth name (Nichols), he married Sarah Sophia Clarke (1837-99) at St Stephen’s Newtown in 1863. He gave his occupation as shipbroker when registering the birth of their first child, Robert Henry Nichols (1864-1914). The birth took place at Burton Cottage, Glebe Rd and was certified by Dr John Foulis. For the birth of Florence Eva (1866-1930), Robert gave his occupation as master mariner. The birth was certified by Dr Renwick. In reality, Robert Fitzgerald Nichols was out of work for long periods during which his father supported him.

The death of Isaac David Nichols in August 1867 brought this security to an end. Neither uncle filled the financial gap. When George Robert Nichols (MLA and a member of the colony’s first ministry) died a decade earlier, a testimonial was raised to support his widow; and the family of Charles Hamilton Nichols (Bell’s Life in Sydney newspaper owner) was poorly provided for when he passed away in 1869. For some reason, Robert Fitzgerald Nichols began calling himself George Robert Nichols, and it was by that name, he was found guilty in May 1870 of stealing wearing apparel and forging a receipt. Awaiting sentencing, he absconded and hid in the Botany Swamps before taking off for Wollongong. He changed his appearance, got some work as a groom and a clerk, forged a receipt and, with the money, travelled as far as Tasmania where he was arrested. (By now, he had added a string of aliases: Alexander Cameron, Walter Davidson, William Henry Mitchell, Robert Nelson.) In Darlinghurst Gaol he became friendly with Alfred Lyster alias James Froud, a white-collar criminal also serving two years’ hard labour.

Meanwhile, his wife, Sarah Nichols, supported her family by sewing, using a machine bought with a subscription raised by a local clergyman. Persuaded that her husband was reformed, he found post-prison employment for Nichols and Lyster with the Sydney Meat Preserving Company at Millers Point. The two men spent hours in each other’s company working out ways to make money.

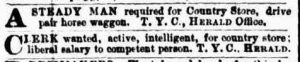

Inspired by stories of a Frenchman who killed young women and sold their clothing, they advertised for workers for a country store. Fortunate were those with few possessions whose applications were unsuccessful. Unfortunate were two new arrivals in the colony: Peter Bridger, a 25-year-old steward from HMS Rosario, and lay preacher William Percy Walker. On two consecutive days, Nichols and Lyster hired a boat from King St wharf and told each victim he was to meet his prospective employer in a house on the Parramatta River and leave his boxed belongings behind to be picked up later.

Bridger’s body was subsequently found in the river near Ryde with a fractured skull and legs bound with a rope attached to a stone. That of Walker was discovered, similarly weighted, in Hen and Chicken Bay. ‘The Parramatta River Murders’ caused a sensation.

Lyster (a defence counsel was Edmund Barton) and Nichols (his life-size figure was displayed in the Royal Waxworks Exhibition) were soon apprehended and found guilty. Nichols’ wife visited him in Darlinghurst Gaol, but his children were denied admission. A bizarre episode followed the men’s execution, witnessed by a crowd of onlookers, on 18 June 1872. The coffins were surreptitiously removed by the undertaker and taken to his Waterloo pub, where the lids were prized open and, for a fee, the contents viewed by drunken customers. Police raided the Morning Star, and the bodies were interred at Haslem’s Creek, now part of Rookwood Cemetery.

Sources: Australian Dictionary of Biography George Robert Nichols (1809-57) entry; Concord Heritage Society; T D Mutch index; NSW Police Gazette 27.3.1872, 10.4.1872; NSW registry of births, deaths, marriages; NSW State Archives & Records; Sands Directories; Trove website.

Posted on 14 September 2021 by Lyn Collingwood

For more information email: heritage@glebesociety.org.au

There are no comments yet. Please leave yours.